Umid Khallyev (32), a former Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty (RFE/RL) reporter from Turkmenistan and the son of the radio’s current contributor Osman Khallyev, has left Turkmenistan with his wife and two children and now seeks political asylum. In 2008 he was thrown out of college in Ashgabat because of his father’s work for the radio and continued to face harassment from the Turkmen security services. In 2009 he was denied exit from Turkmenistan to Canada, where he wanted to pursue higher education. Since then for many years he remained blacklisted.

In his interview with Alternative Turkmenistan News he described his experience working as an independent journalist and why he decided to leave his homeland for good.

— After my military service I repeatedly applied to the Turkmen National Institute of World Languages, but without a bribe they refused to take me. Back in those years hardly anyone could enroll in college without money and only a handful of lucky ones would make it through.

Finally in 2007 I made it through too after having learned by heart the Rukhnama [former President Niyazov’s book, until recently one had to take a test on Rukhnama even to get his driver’s license] and the high school curricula of English and Turkmen languages. I became a freshman in the Arabic language department.

I was a good student; my teachers valued me and often sent me to interpret for foreign guests at various international conferences that were held in Ashgabat. However, in 2008 they let me go. The official reason was my alleged poor academic progress, but the real reason was that my father, Osman Khallyev, was working for RFE/RL. Even when I was in college officers of the Ministry of National Security (MNS) would come to me and offer a deal: either I urge my father to stop his work for the radio, or they kick me out of school, which they eventually did.

— Did you tell your father about these offers?

— Yes, certainly. My father wanted to quit his job but his colleagues in Prague promised to do everything to send me to study in the U.S. So he continued his work, I was expelled from college, but no help from the radio followed.

— You said you were a good student. Did you try to challenge your dismissal?

— No, I didn’t. I knew it would be useless. After that I decided to study abroad, took a TOEFL test and sent my applications to four universities in the U.S. and Canada. Soon I received a letter from Carleton University in Ottawa, which said that they would take me and even take 40% off tuition. The rest of the tuition, they said, I would pay by working on campus. So I made up my mind and on January 16, 2009 I showed up at Ashgabat’s airport to fly out to Turkey for my Canadian visa. However, at the airport’s passport control I was told that I couldn’t leave the country: I was blacklisted with no explanation.

— And then you turned to the Immigration service…

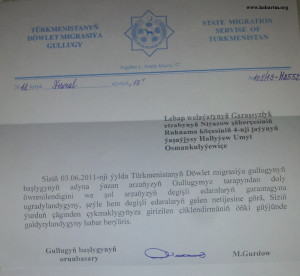

— Yes. I sent them around 10 letters, but their answers were identical: “Your request has been forwarded to relevant state bodies, and according to their responses your travel ban remains enforced.»

Umid has sent us several copies of letters from the Immigration Service of Turkmenistan. They bear various dates: November 2009, January, February and April 2010, March and April 2012.

— At that time I had a family to feed, but no matter how hard I tried, no one would hire me. Then I took the offer of RFE/RL Turkmen service to work for them as a freelance reporter. We signed a contract and in January 2012 I began working for them.

My stories were mostly about social hardships of Turkmen citizens: unavailability of train tickets, poor road infrastructure and other similar issues of Lebap province residents. In addition to articles, I also produced audiovisual content. Given the Turkmen circumstances, it was quite a risky task.

— Have you ever been harassed by the government of Turkmenistan because of your work?

— Oh, constantly. Many times the police detained me. There were so many detentions and threats that I can’t even tell the exact number. One of them I remember very well though. It was on September 1, 2013 in Turkmenabat, where I came to photograph an organized bicycle ride. On that day such rides were held in all parts of Turkmenistan. I came to Turkmenabat early in the morning and started to photograph the ride participants. Later I walked down to the Rukhiyet Palace where all cyclists were told to gather. The whole walk I continued to record on camera until a police officer noticed me and requested I stop. I didn’t resist, I told him I was an RFE/RL reporter and that I was only doing my work. The officer pulled out his phone, called someone and reported that he’d caught a spy! As though the spy, meaning me, was filming the President’s residence on Bitarap Turkmenistan Street.

A few minutes later two men came over in a Toyota, put me in their car and took me to the regional police department. On the way there they introduced themselves as officers of counter terrorism and the organized crime department of the police. In the police station they took me straight to the head of that department. The moment I entered his office, the chief began to yell at me, saying that he is sick of us (my father and me) and that soon we would end up in prison. He took away my camera, but didn’t erase the photos because they only showed the cyclists in the street and nothing more than that. He passed the camera over to his other colleagues and all of them noted that the photos were actually nice and beautiful.

After that in one of the offices they began to interrogate me: how long have I been working for the radio, why I work for them, how much I get paid, etc. One of them suggested I better switch from journalism to trade. In the end they started to praise the government, that at least it is safe in Turkmenistan and there is no war and so forth. A few hours later after such psychological pressure they allowed me to go but said that this would be my last warning, that next time they would charge me with spying. It took me several days to recover from this emotional pressure.

There were also attempts from security services to buy me out. In April 2012 two men from the counter terrorism department came over to my home and offered assistance in finding me a “good job.” Working for RFE/RL is high treason, they said.

Security service officials also offered me help with finding a job, but I’d always refuse and try not to talk to them too much as I knew it wouldn’t lead to anything good. I know of several examples when people were cornered because they were unable to find a job in Turkmenistan because of their beliefs or civic stand. They’d accept offers from security services and would be fully dependent on them, betraying themselves and their values.

I was mostly threatened over the telephone. Security officers could call me any time of day or night and say that sooner or later they would deal with me. They reminded me that though I work for a foreign radio, I still remain a Turkmen citizen and that the Criminal Code applied to me. They said that I should remember one thing: if an order comes from “above,” then they will always find a reason to lock me up for a long time.

— How and when did you eventually manage to leave the country?

— In December 2012 I received an official invitation from RFE/RL to visit Prague and participate in a training on journalism. Since my phone line was wiretapped and all web visits were constantly monitored, the security services learned about the invitation and called my father to say that I would not have troubles leaving the country. And it turned out to be true. That time it was my first foreign trip and I was very happy! I was 30.

I spent three months in Prague. Upon my return nobody bothered me for two months until my new stories started to appear on RFE/RL. The phone calls and threats resumed as the issues I raised in my articles sharpened. After I filmed young children picking cotton in a field and sent the file to the radio, they called me and demanded I not shoot such things in the future.

— Did you try to leave the country again for business or pleasure after your trip to Prague? Were there other cases of your travel ban?

— In December 2013 I went to Istanbul for a month to write a series of stories about the living and working conditions of illegal Turkmen labor migrants. I wasn’t denied exit, but they held me at the passport control for about two hours. The immigration control officer studied my profile on his computer with wide-open eyes. I could see surprise and horror in his eyes at the same time. He kept calling someone on the phone and asking him different questions and clarifying his answers. Ultimately, I boarded the plane just minutes before its departure.

At the end of April 2014 my family and I urgently had to leave Turkmenistan for my elder son Abdulla’s health condition. He has congenital heart disease Tetralogy of Fallot with several abnormalities. The child urgently needed surgery. The first thing we did was to turn to the heart disease center in Ashgabat, but the doctors there said they didn’t perform such difficult surgeries.

We found the right clinic and doctors in India, and on April 26 we flew to New Delhi. At that time in the airport the immigration officers again asked us to step aside and wait until they checked our profiles. It took them a very long time; they again called someone, took our passports to a separate room, then brought them back. It’s hard to describe how my wife and I felt that moment, because the life of our child depended on their decision…

— How did the surgery go?

— It went fine. My son slowly got better, but a few months later his pulse started to drop. We again had to fly to India. I was worried and nervous, I thought that this time they wouldn’t let us go, because you can’t leave Turkmenistan if you intend to seek medical help abroad. Plus I was a “spy.” But despite a long waiting time at the airport and the routine with checking profiles, we were finally allowed aboard the plane. This was an exceptionally stressful experience, I was afraid that we wouldn’t get our child to the hospital alive. In New Delhi they implanted a pace maker in his heart.

— Where are you now?

— In India we decided that going back to Turkmenistan was a big risk for me and my family. We simply couldn’t risk the health of my ill child every time. There was no confidence at all that we would make yet another trip overseas, that they wouldn’t decide OK, that’s enough! Just as they did it to me from 2009 till 2012, or as in 2008 they banned my father from travelling to Kyrgyzstan for a journalism training.

On November 14 we flew from New Delhi to Dushanbe, applied there for Kyrgyz visas and on November 30 at night we arrived in Bishkek. The next morning we went to the local UNHCR office and submitted papers for asylum. There they told us to submit a similar request to the Kyrgyz Ministry of labor, migration and youth, which we did the same day. We haven’t received any answer yet; it’s been almost four months now since we are here.

— How is your child’s current health condition?

— Now it is fine. The Indian doctors told us that the pace maker should be checked every three months or at least twice a year. In Bishkek I turned to the public organization “Counterpart-Sheriktesh” that provides free medical help to refugees. The organization’s staff cardiologist told us that there are no state or private clinics in Kyrgyzstan capable of checking the pace maker. He suggested we immediately turn to the UNHCR and ask to speed up our asylum request. We did it but heard back that our refugee status hasn’t been approved yet. According to the rules, if the current state cannot provide necessary medical services, then refugees can be sent to a third country.

— Did you seek support elsewhere in your situation?

— Yes, I wrote to many international organizations, including Human Rights Watch, Freedom House, Amnesty International, Reporters without Borders (RSF), Committee to protect Journalists (CPJ), Norwegian Helsinki Committee, the Rory Peck Trust [NGO that provides support to journalists and their families in crises] and a few others. I only heard back from RSF and the Rory Peck Trust: RSF is trying to do something but there is no progress yet, and the Rory Peck Trust promised to help us financially. I filled out the form they sent me but didn’t hear anything back. I am hoping for the best.

— Have you been getting threats from the Turkmen security services ever since you left the country? Do your relatives get any pressure to make you return?

— While I was away from Turkmenistan I didn’t get any threats. I can’t comment if there’s pressure on my relatives in Turkmenistan or not. On the telephone they immediately cut me off when I start asking about it. They say they are fine. It is possible that they are just saying this.

— Where would you want to live, in which country?

— In a country where rights and freedoms of citizens are respected.

— What would you do once you got asylum?

— Despite my age, I’d first of all like to get higher education. I like journalism very much and would like to continue in it. I’d like to work for the benefit of the country that hosts me and my family.

——

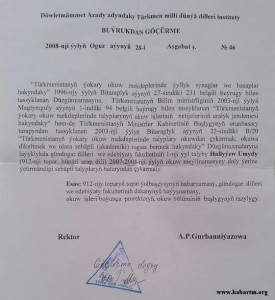

Translation of college dismissal statement:

«Turkmen National Institute of World Languages named after Dovletmammet Azady

ORDER STATEMENT

June 28, 2008, Ashgabat, №46

In accordance with Clause «On final year examinations in higher schools of Turkmenistan», approved by Decree №231 on December 27, 1996; Clause «On intermediate academic progress of students of higher schools of Turkmenistan», approved by Decree №94 of Ministry of Education Turkmenistan of May 1, 2003; as well as in accordance with Clause B/20 «On the dismissal of students of higher schools of Turkmenistan, their restoration and provision of reasonable (academic) leaves», approved by Deputy Head of Ministers’ Cabinet of Turkmenistan on December 22, 2003, dismiss Umid Khallyev, freshman of Department of Oriental languages and literature (group №912, «Arabic language» concentration) for insufficient implementation of 2007-2008 academic program.

Reason:

Statement from head of group №912, solicitation from head of Department of Oriental languages and literature; consent from Dean of Academic Affairs, head of academic unit.

Rector А.P. Gurbanniyazova

«Statement correct» [stamped, signed]»